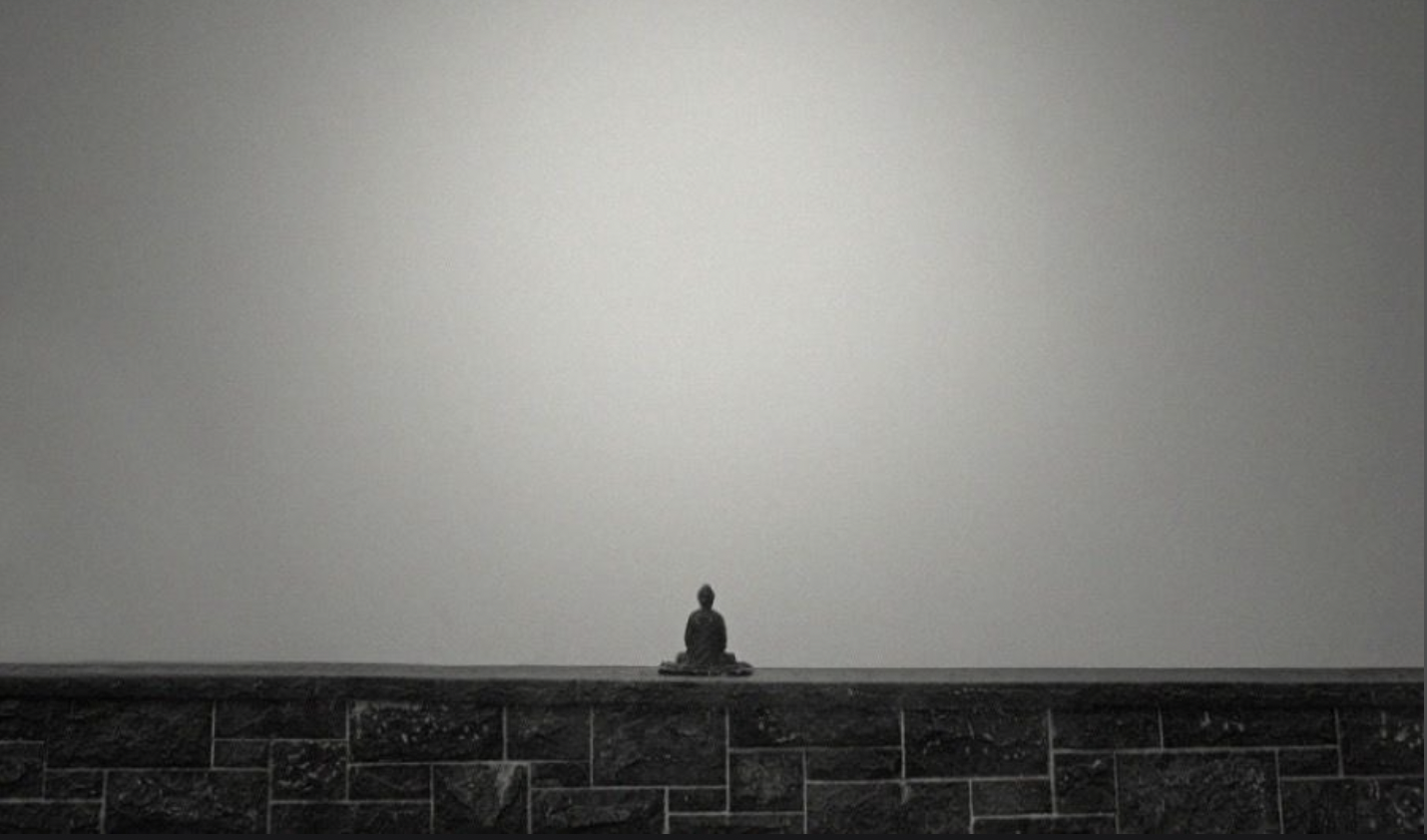

What is the Essence of Emptiness?

Emptiness stands as the cornerstone of Buddhist philosophy, setting it apart from other belief systems. Buddhism teaches that neither individuals, nor other sentient beings, nor any aspect of the cosmos possess an enduring, distinct, and autonomous essence, such as a core, soul, or identity. Another perspective frames this as interdependence: every relative phenomenon emerges solely through external causes and conditions.

Do I truly exist?

Engaging in spiritual pursuits inevitably confronts us with the enigmatic depths of our own being. We emerge into existence within human form, yet what animates us, propelling life and shaping the world around us? Throughout history, profound spiritual teachings consistently challenge our conventional understanding of selfhood. Yet, does this negate the existence of a self entirely, or does it beckon us toward a quest for an authentic essence?

The notion of “no self” has endured as a prominent but misconstrued Buddhist concept. It persists due to its superficial resemblance to the teaching of anatta, or not-self, a pivotal aspect of the Buddha’s teachings aimed at dispelling attachment. While the Buddha neither confirmed nor refuted the existence of a self, he illuminated the mechanisms by which the mind constructs various identities—what he termed “I-making” and “my-making”—in its pursuit of desires.

Two Truths

To understand selflessness, you need to understand that everything that exists is contained in two groups called the two truths: conventional and ultimate. The phenomena that we see and observe around us can go from good to bad, or bad to good, depending on various causes and conditions.

Many phenomena cannot be said to be inherently good or bad; they are better or worse, tall or short, beautiful or ugly, only by comparison, not by way of their own nature. Their value is relative. From this you can see that there is a discrepancy between the way things appear and how they actually are. For instance, something may—in terms of how it appears—look good, but, due to its inner nature being different, it can turn bad once it is affected by conditions. Food that looks so good in a restaurant may not sit so well in your stomach. This is a clear sign of a discrepancy between appearance and reality.

These phenomena themselves are called conventional truths: they are known by consciousness that goes no further than appearances. But the same objects have an inner mode of being, called an ultimate truth, that allows for the changes brought about by conditions.

A wise consciousness, not satisfied with mere appearances, analyzes to find whether objects inherently exist as they seem to do but discovers their absence of inherent existence.

In the same way, when the thought “I” arises in dependence upon mind and body, nothing within mind and body—neither the collection which is a continuum of earlier and later moments, nor the collection of the parts at one time, nor the separate parts, nor the continuum of any of the separate parts—is in even the slightest way the “I.” Consequently, the “I” is merely set up by conceptuality in dependence upon mind and body; it is not established by way of its own entity.